Today’s best urban designers are using innovative techniques to mitigate stormwater runoff pollution. Here’s how.

STEP ONE: KNOW THE STREET’S GEOMETRY

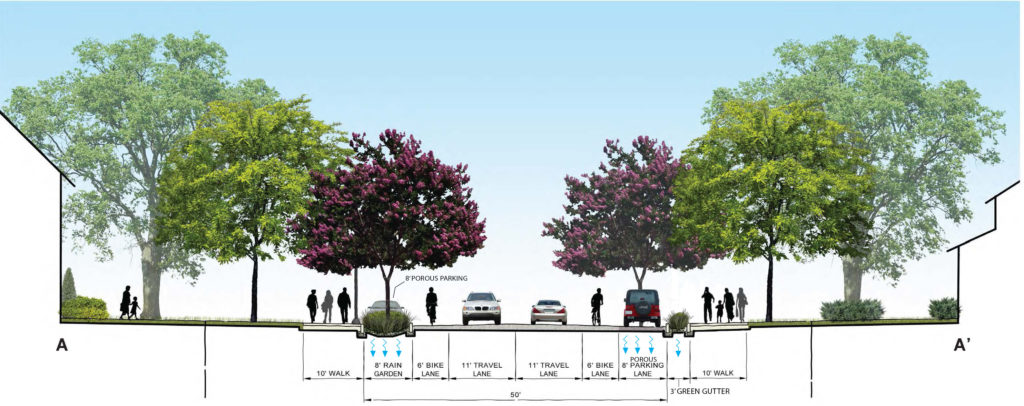

When planning a green street, designers need to know what can fit within the existing cross section or right of way (ROW) of your street. The width of the right of way will determine which green street strategies can be used.

In the past, roadways have been designed to move vehicles through them as fast as possible. Today, roadways are often designed or redesigned to accommodate multiple modes of transportation—vehicles, bikes and pedestrians—sometimes even light rail. To keep cyclists and walkers safe, designers are including “traffic-calming devices” that slow traffic down. This concept is called “complete streets.” Using this complete street concept, travel ways can be tightened to 11 feet with a two-foot shoulder and, if desired, a six-foot bike lane.

Complete streets are a great innovation. Not only do they provide space for eco-friendly modes of transportation, they also allow for the use of green street techniques—the space between lanes, bike paths and pedestrian walkways can collect runoff and filter pollution. What’s more, these areas build community character and personality.

STEP TWO: DETERMINE SOIL POROSITY

To ensure that green streets work as intended, designers must know the location’s soil type. A percolation test will verify the soils’ porosity. Having less porous soils does not rule out green infrastructure, but it may require modification of the design and perhaps amended soils.

Porous soils should have a minimum eight-inch sub-base of open-grades , with crushed angular stone one-and-a-half to two-inches thick. This sub-base should then be topped with six inches of base material—open-graded crushed angular stone that is a half-inch to one-inch thick. The base material is then topped with a planting medium or, for pervious pavements, a setting bed—an inch of sand in which to set high-density pavers.

While porous soils allow for vertical filtration, less porous, non-porous, or non-exfiltration soils require horizontal filtration. These soils will use the same cross section as more porous ones, but need to include an underdrain or an overflow pipe (or both) to filter stormwater as it flows toward storm drains that tie into the local storm sewer.

STEP THREE: KNOW THE OPTIONS

There are several green infrastructure strategies that can be employed.

Bioretention Curb Extensions: Sometimes called “bulb-outs,” these extensions are unpaved or partially paved areas that extend into the roadway beyond the existing curb line. They are most commonly used at intersection or at mid-block crossings. These are the most visible areas and can increase the aesthetic of the street. Placing them so that they receive the most stormwater runoff is key. Openings in the curb will allow the stormwater to enter the bioretention curb extension.

Sidewalk or Urban Rain Gardens: When there is sufficient room on sidewalks, a good alternative to curb extensions is using sidewalk or urban rain gardens. Using the same premise of the curb extensions, these can be much larger and have a greater visual impact on your streetscape.

Green Gutters: When space is limited, a two-foot strip of a bioretention area just behind the curb can be used to infiltrate stormwater while providing some additional plant material to the streetscape. If there is on-street parking, the designer should provide a means of access from the parking stall to the sidewalk.

Porous Pavements: There are a number of pavement types that can be used. Porous asphalt and concrete are now becoming more available. Precast concrete pavers have been the most used to date and can increase the aesthetics of the street. As with all these green strategies, placement is important. The most common use of porous pavements is in the parking bays of on-street parking. Most roadways are crowned, so this placement allows stormwater to sheet across the travel ways to the porous pavement, where it is infiltrated.

STEP FOUR: SELECT HARDY PLANT MATERIALS

One myth about planting bioretention areas is the need to use plant material that can withstand moist soils. Green street plants often go weeks without water, so plants need to withstand both extended wet and dry periods. The best plants vary by area—the best choices are often native—so consult with a local landscape architect for planting recommendations.

STEP FIVE: PLAN FOR MAINTENANCE

Once the green street is constructed, it is critical to know how it is going to be maintained. If porous pavements are used, the community should invest in a vacuum street cleaner to aid in keeping the pavement’s openings flowing. For the bioretention areas, if city or town staff are not available, consider enlisting local building merchants or homeowners to be your bioretention stewards. A great example is the green street steward program run by the city of Portland, Oregon, which is one of the first communities to install green infrastructure and has done the most research in what works.

Thomas Tavella, FASLA, is the president of the American Society of Landscape Architects and the president of Tavella Design Group, LLC in Orange, Connecticut.